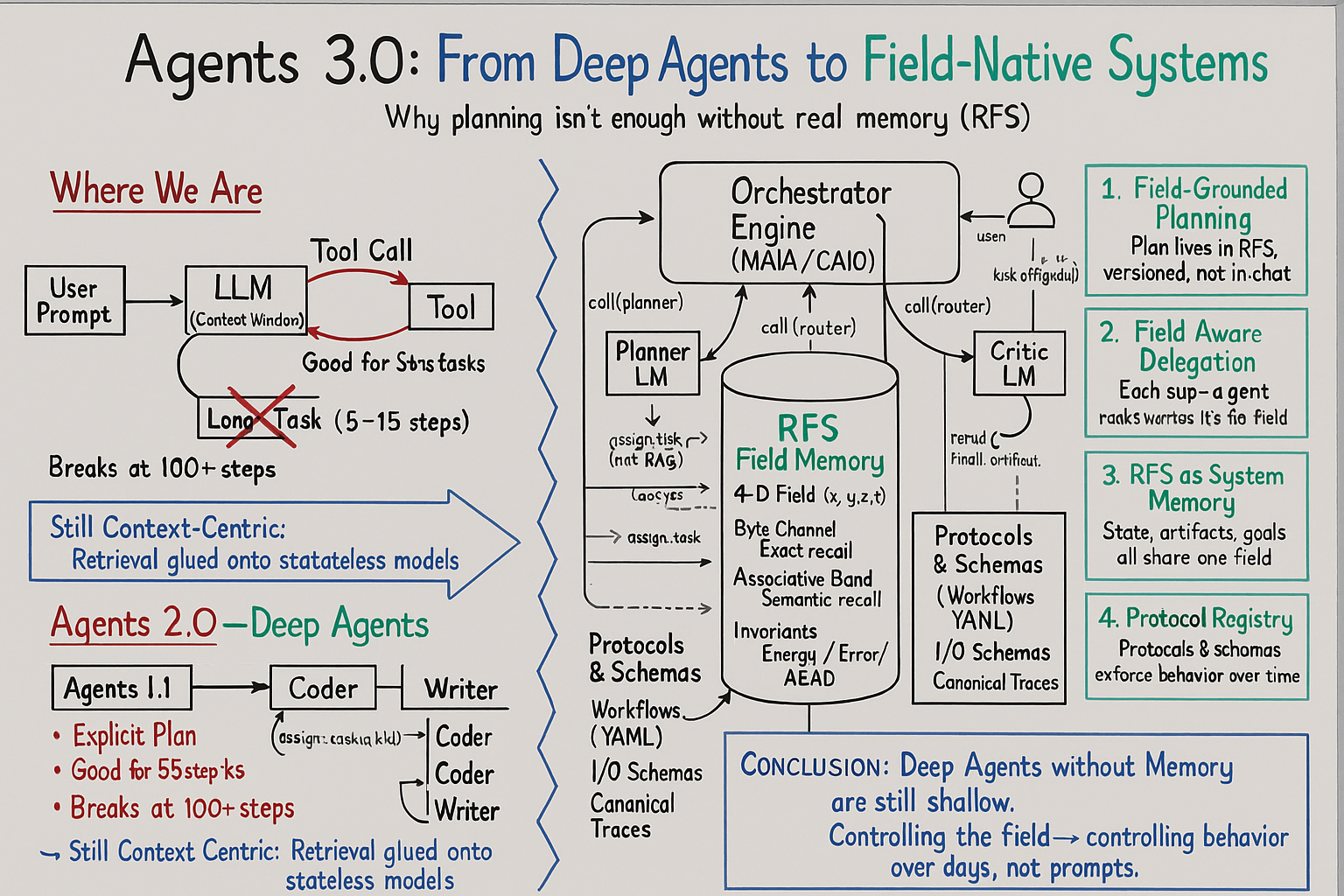

Agents 3.0: Deep Agents Need Deep Memory

Philipp Schmid wrote about "Agents 2.0" last month, and he was right about one important thing: the naive "LLM + tools" pattern was never going to cut it. You need planning. You need sub-agents. You need persistent state, files, long prompts, orchestration. That whole movement was the industry finally admitting that agents are systems, not toys.

But there's a quieter truth sitting underneath all of that:

You can fix the loop and still have a system with no memory.

Most of what people are calling "Deep Agents" today are just better workflows wrapped around the same brittle core. The brain is still the context window. The vector database is still an accessory. The filesystem is a junk drawer. The plan is a markdown file everyone pretends is a mind.

If you want agents that can run for days or weeks without forgetting what they did, contradicting themselves, or hallucinating their own history, that's not enough.

Agents 2.0 fixed coordination.

Agents 3.0 have to fix memory.

The Real Beginning: When the System Fell Apart

This is the part that always gets mis-told about my background.

I wasn't quietly building agent systems in 2017. I didn't come out of a decade of ML research or spend years in some lab fine-tuning large models. My story with agents only really starts in 2024–2025, when I tried to build real systems with LLMs—and they broke.

Not once, not occasionally, but in a way that was repeatable and predictable:

You'd design a multi-step workflow.

You'd add tool calls and some careful prompting.

You'd give it a plan and some structure.

And then, as soon as you stretched it across time, it would collapse.

The model would contradict conclusions it had written three steps earlier. Artifacts from yesterday would vanish from its world. Retrieval would feel sharp in one moment and completely random the next. You couldn't reconstruct a multi-day trajectory without spelunking through logs and guessing.

Recovery wasn't "rewind to a stable state."

Recovery was "start a new run and hope it goes better."

Everyone treated this as a limitation we just had to tolerate. I didn't. I wasn't willing to pretend that "forgetting everything beyond a few thousand tokens" was a minor implementation detail.

At some point the pattern became obvious: there was no such thing as memory in these systems. There was storage. There were indexes. There were prompts. But there was nothing that deserved to be called memory.

So I stopped trying to be clever with prompts and started doing the only thing that felt honest: I went down to the math.

Mathematical Autopsy: The Only Way Forward

Vibe coding works fine when you're building demos. It completely breaks when you ask a system to stay consistent under pressure.

The only way I could get anything to hold together was to force a different sequence:

Define the problem precisely.

Extract invariants.

Describe operators and their constraints.

Prove the behavior in notebooks.

Wrap those proofs in CI.

Only then write code.

That pipeline eventually became what I now call Mathematical Autopsy—MA. It wasn't invented as a "framework." It was a coping mechanism.

LLMs couldn't keep invariants in their head. Prompts couldn't reliably enforce rules. Retrieval couldn't guarantee that what came back was stable or even relevant enough over long horizons.

The result was simple: I stopped trusting the model's internal state and started trusting only what I could represent explicitly—mathematically, structurally, and in code paths that could be tested.

Once I did that, the conclusion was unavoidable:

If you don't have a real concept of memory, everything else is decoration.

That's where Resonant Field Storage came from.

RFS: Memory as a Field, Not an Index

Resonant Field Storage, RFS, did not start as a clever idea for a startup pitch. It started as the thing I needed in order for any of this to work at all.

I needed a substrate that could:

-

remember exactly what happened, not just "something similar,"

-

remember semantically what was related,

-

track how things evolved over time,

-

enforce constraints and invariants,

-

bound error and drift,

-

detect contradictions and incoherence, and

-

support recovery as a first-class operation.

No vector database, no filesystem, no prompt pattern could do all of that. Not in a way that you would trust.

So I stopped treating memory as an index and started treating it as a field.

RFS is a 4-D memory substrate: three spatial dimensions plus time. Information lives as structured waveforms. There is a byte-channel for exact recall—artifacts, code, logs, documents—and an associative band for semantic recall, where similarity and resonance actually mean something.

Time isn't an afterthought; it's baked into the coordinate system. You don't just store facts, you store trajectories.

On top of that, the field is governed by laws: decay equations that shape how information fades or persists, invariants that tie energy and error together, AEAD so you can't silently corrupt state, and a completion operation—field-completion—instead of "retrieve a few chunks and stuff them back into the prompt."

RFS wasn't built to compete with vector DBs. It was built because they were fundamentally the wrong shape for memory.

And once you have a real memory substrate, you can't keep pretending that "the agent is the LLM."

Agents 3.0: The System Is the Agent

Agents 2.0, including the ones in Philipp's piece, implicitly assume that the agent is the LLM wrapped in some scaffolding.

Agents 3.0 flip that assumption:

The agent is the system.

The LLM is just one operator inside it.

In a field-native architecture, the center of gravity moves:

-

from "prompt and tools" to "field and operators,"

-

from "context window" to "system state,"

-

from "chain-of-thought" to "time-indexed trajectories,"

-

from "mega-prompt" to "protocols and schemas,"

-

from "rerun the workflow" to "rewind and recover."

Once you treat the field as the source of truth, everything else shifts.

Planning as State, Not a Markdown To-Do

In Agents 2.0, planning lives in a file somewhere. The agent writes a plan, maybe updates it, and everyone hopes the model remembers to follow it.

In Agents 3.0, the plan is a structured, versioned object in the field.

The Planner isn't relying on what it "remembers" from the last response. It reads the current goal, constraints, and world state directly from RFS. It chooses a protocol from a registry of workflows stored in the same field. And it writes back a plan object—steps, dependencies, expectations—that becomes part of the trajectory.

Every update is a new version. Every failure is captured as an event, not a feeling. You aren't trying to coax the model into honoring a to-do list; you are evolving a piece of system state under explicit rules.

Planning stops being a prompt trick. It becomes architecture.

Delegation as Dataflow, Not Prompt Passing

The classic picture for Deep Agents is an orchestrator prompting sub-agents: "Here, you're the Researcher, you're the Coder, here's your context window, go."

In Agents 3.0, those roles are still there, but the communication pattern changes completely.

The orchestrator writes a task object into the field. That object points at the relevant slice of state, the applicable plan segment, and the schema for what a valid output looks like. A Researcher, Coder, or Writer reads that task from the field, does the work, and writes their artifacts back into the field with the same schema.

No one is passing prompts around by hand. No one is hoping the right subset of context is glued into the right message. Delegation is just data flowing through a shared substrate.

Once you do that, you can swap out models, swap out tools, re-run tasks, or inspect the entire trajectory without losing the thread.

Retrieval Dies; Field-Completion Takes Over

The standard pattern for "memory" in Agents 2.0 is still retrieval:

embed, store, query, hope the right chunk returns.

Anyone who has built a non-trivial system with this pattern knows what happens at scale: relevance drifts, collisions pile up, and subtle bugs hide in whatever didn't get retrieved.

In a field-native system, the operation is different. You don't yank out a few strings and throw them back into the context window. You excite the field with a query waveform and get back a completion that is constrained by the invariants of that field.

The field doesn't just tell you "this text looks similar." It answers inside the rules you've given it: bounded error budgets, energy constraints, integrity guarantees, temporal structure.

Memory stops being "whatever the vector DB returns."

It becomes "whatever the field, under its laws, allows to be recalled."

That sounds abstract until you try to maintain coherence over weeks. Then it becomes the only thing that matters.

Protocols as Law, Not 6-Page Prompts

Another hallmark of Agents 2.0 is the mega-prompt: a multi-page block of text describing how to think, how to plan, how to name files, how to call tools, how to collaborate with the user. It works—until it doesn't, and you have no idea which part failed.

Agents 3.0 move that logic out of prompts and into a protocol registry inside the field.

Protocols define what a workflow is allowed to do: preconditions, postconditions, required artifacts, success criteria. Schemas describe the shape of the objects involved. Canonical traces show what a good run looks like. All of this is stored and versioned like code.

Models don't memorize behavior; they look it up. They execute against law, not vibes.

That makes behavior auditable. It makes upgrades possible. And it makes it much harder for an agent to "succeed" in a way that's quietly wrong.

Trajectory and Recovery as Native Operations

Both 1.0 and 2.0 agents are terrible at recovery. Once the context is a mess, there's no principled way to unwind it. You end up rerunning the whole thing and hoping it goes differently.

In a field-native architecture, every meaningful step—every plan version, task, artifact, decision, and correction—is written into the field as part of a time-indexed trajectory.

A Critic model can read that trajectory, not just the last few messages. It can see loops. It can see contradictions. It can see where invariants were violated or where quality dropped. And it can trigger the system to branch, roll back to a prior state, or replay a segment with different parameters.

You don't recover by trying a new prompt. You recover by rewinding and operating on history like data.

A Simple Example

Take the standard example everyone uses for Deep Agents: "research quantum computing and write a summary."

In an Agents 2.0 setup, the orchestrator writes a to-do list somewhere. The Researcher sub-agent does some searches and writes notes to disk. The Writer reads those notes and writes a quantum_summary.md. Somebody checks a box in the plan.

It works, until you ask that system to plug this work into something larger or come back to it three days later.

In an Agents 3.0 system, the flow looks very different—even though the surface request is the same.

An interface agent writes a goal and constraints object into RFS. A Planner reads the field, chooses a "research-and-synthesize" protocol, and writes a structured plan object back into the field. A Router creates task objects referencing the relevant state, protocol, and schemas.

The Researcher excites the field, gets back a completion that includes relevant prior work and context, does any external search it needs to do, and writes both raw notes and a structured summary into the field. The Writer reads those artifacts and the plan, produces the summary, and registers it as the canonical user-facing narrative for that goal.

A Critic inspects the trajectory and artifacts against the protocol. If something is off, it doesn't shrug. It writes a failure node, and the system revises the plan.

The chat UI at the end is almost an afterthought. It's just a view onto what the field now believes is true.

The Real Shift

Agents 2.0 were a necessary step forward. Philipp's piece captured that moment well: we needed to move beyond "LLM with a bag of tools" and into something that at least looked like an architecture.

But that shift didn't fix the foundational problem. It gave us better loops around a system that still has no real memory.

Agents 3.0 start from a different premise:

-

memory is not an implementation detail,

-

the field is the source of truth,

-

models are operators over that field,

-

behavior lives in protocols and trajectories, not just prompts,

-

recovery is an operation on state, not a rerun of history.

If Agents 1.0 were loops, and Agents 2.0 were workflows, then Agents 3.0 are systems:

systems with a real memory substrate, real invariants, real time, and a real notion of self-consistency that survives longer than a context window.

Deep agents without deep memory will always be shallow.

Field-native systems are how you start changing that.